Chapter 10 – River Avon (Case Study)

The Quaternary deposits in the Avon valley include clay-with-flints, head, gravelly head, river terrace deposits, brickearth, alluvium and occasional peat. Clay-with-flint is a residual deposit created by modification of Palaeogene sediments and the solution of the underlying chalk, deposited considerably earlier than the river terrace deposits.

The exact age is uncertain, but clay-with-flint deposits in south-west England are likely of Pleistocene age (Gallois 2009). Clay-with-flint is mainly found on the flats of hilltops. Older head deposits, associated with clay-with-flint sediments, formed through solifluction and solution of the latter and the underlying bedrock. It is often found on the upper valley slopes. Further down the valley ‘head gravel’, ‘gravelly head’ and ‘head’ are found, deposited by fluvial transport, hill wash, hill creep and solifluction (Barton et al. 2003; Hopson et al. 2007).

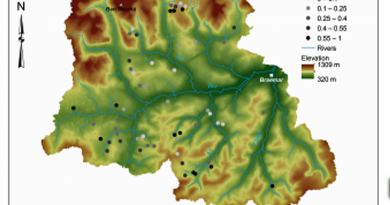

The fluvial deposits in the area form a flight of 14 river terraces. The highest terraces, up to 100m above the Avon valley floor, spread up to 12km wide from the present-day river axis. The lower terraces in the Avon catchment are 6 to 3km wide and are found alongside and below the present-day river (BGS 1991, 2004, 2005). The massive extent and limited altitudinal separation between the highest terraces point to the draped deposition of these terraces over the landscape (Clarke and Green 1987).

The terraces are of relatively constant thickness along the valley. This is typical for systems where sediment overloading from upstream and input from tributaries to the main valley occurs (Blum and Tӧrnqvist 2000). This is probably combined with lateral erosion and redeposition of fluvial sediments (Brown et al. 2009a, b).

This mechanism could explain the progressive restriction of floodplain width between each erosion-aggradation phase (Brown et al. 2010). The high number of terraces may indicate that terrace formation in the Avon valley cannot directly be linked to MIS cycles as suggested in the model of terrace formation developed by Bridgland (2000).

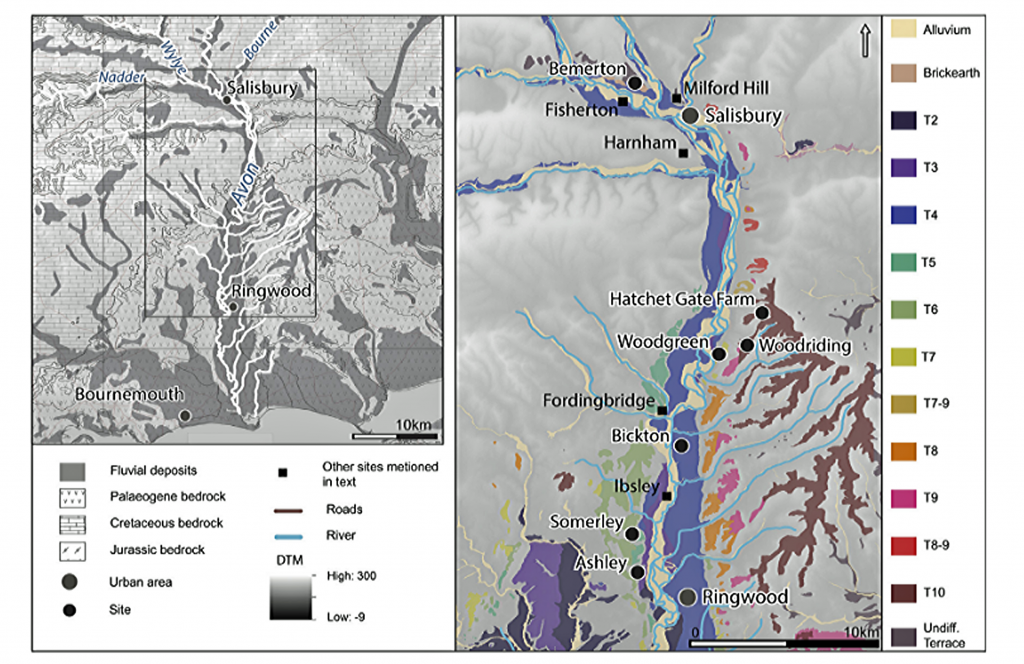

The Avon terraces, the pre-Quaternary geology is briefly discussed In a Maddy et al., publication ‘Crustal uplift in Southern England: evidence from a river terrace records’ Illustrated that there were several terraces from the river Avon still visible in the Hampshire basin which they called T5 – T10. ‘Little has been done to determine the age of either the terrace sequence or the older River Gravels in the Avon Valley’.

‘However, interglacial sediments within the two lowest terraces of the Solent have been assigned to OIS 7, and OIS5e (Allen et al., 1996) Organic Remains of probable Ipswichian(OIS 5e) age (Barber and Brown, 1987), and probable early Devensian age (Green et al.,1983) have been described from sediments underlying low-level terraces within the Avon valley, but at higher elevations in the valleys of the Avon and its tributaries, no organic remains have ever been described’.

This dating of river terraces is more confused when a recent publication called: ‘Pleistocene landscape evolution in the Avon Valley, southern Britain: Optical dating of terrace formation and Palaeolithic archaeology’ by Egberts et al., 2019. Produced a set of results that questioned the way previous Geologists have dated these river terraces.

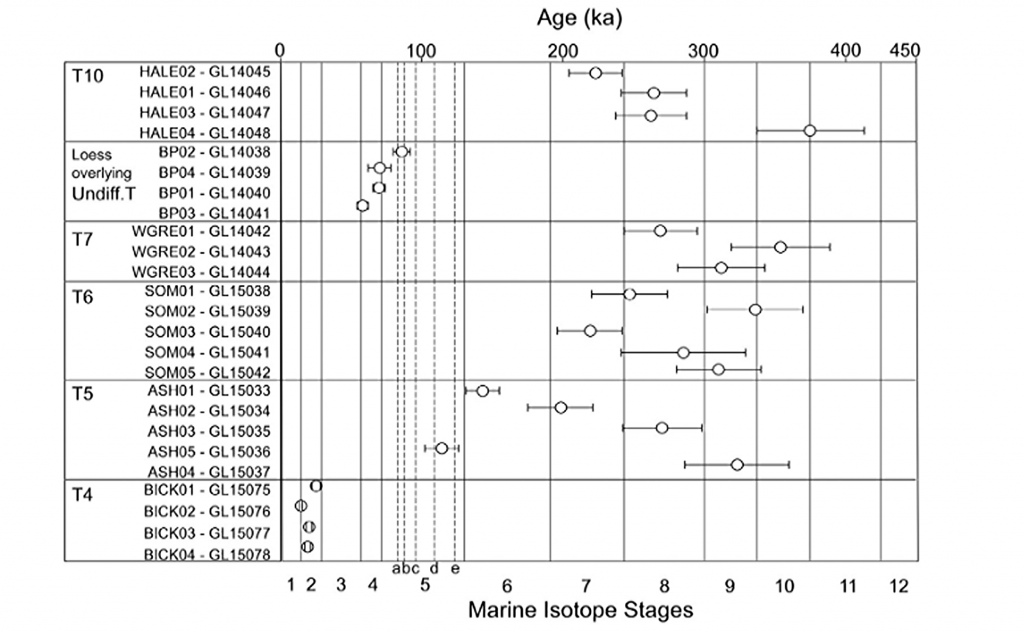

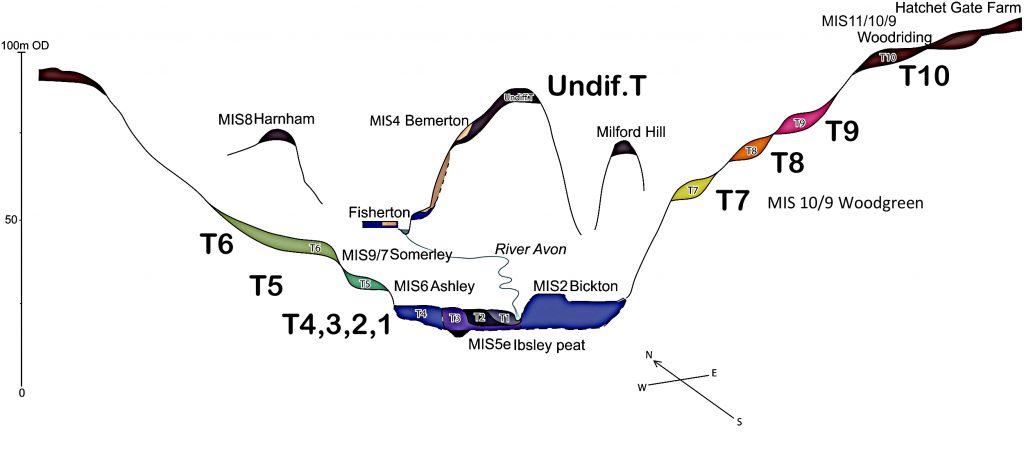

Fig.60 presents the OSL results per terrace and in relationship to the MIS stages. The schematic valley cross-section is shown in Fig. 61 is also based on the 3Dmodel of the superficial geology of the Avon valley, built in ‘Rockworks’ is based on BGS borehole data. The OSL ages for T10-7 suggest deposition during or before MIS10/9 (Fig. 60). They are broadly in agreement with, but potentially offer a refinement of, previously proposed relative chronologies used for dating the archaeological record of T7 and the calculation of regional uplift and incision rates.

The first observation you can make from these results is that they are ‘inconsistent’ at best and almost random at worst? It is clearly not what was expected by the team as the supposed oldest terrace at the top T10 (at the height of 102m OD. Fig 61) was laid (according to the OSL dating method) over a 200,000-year period. This is compounded with T7 terrace (58m OD) being dated BEFORE T10?? But the most compelling evidence of the problems (with this old dated terrace hypothesis of yesteryear) is the Loess Terrace at (77m OD – Undif. T) was laid during the LGM, as was T4 which has the youngest dates.

The authors attempt to explain this remarkable result by suggesting “Therefore, more plausible explanations for this discrepancy between the age estimate of T4 at Fisherton and that at Bickton are either that T4 at Bickton includes sediments ‘reworked’ during more recent fluvial processes or that T4 is a ‘compound’ terrace exhibiting differing depositional behaviour in the upper and lower catchments.”

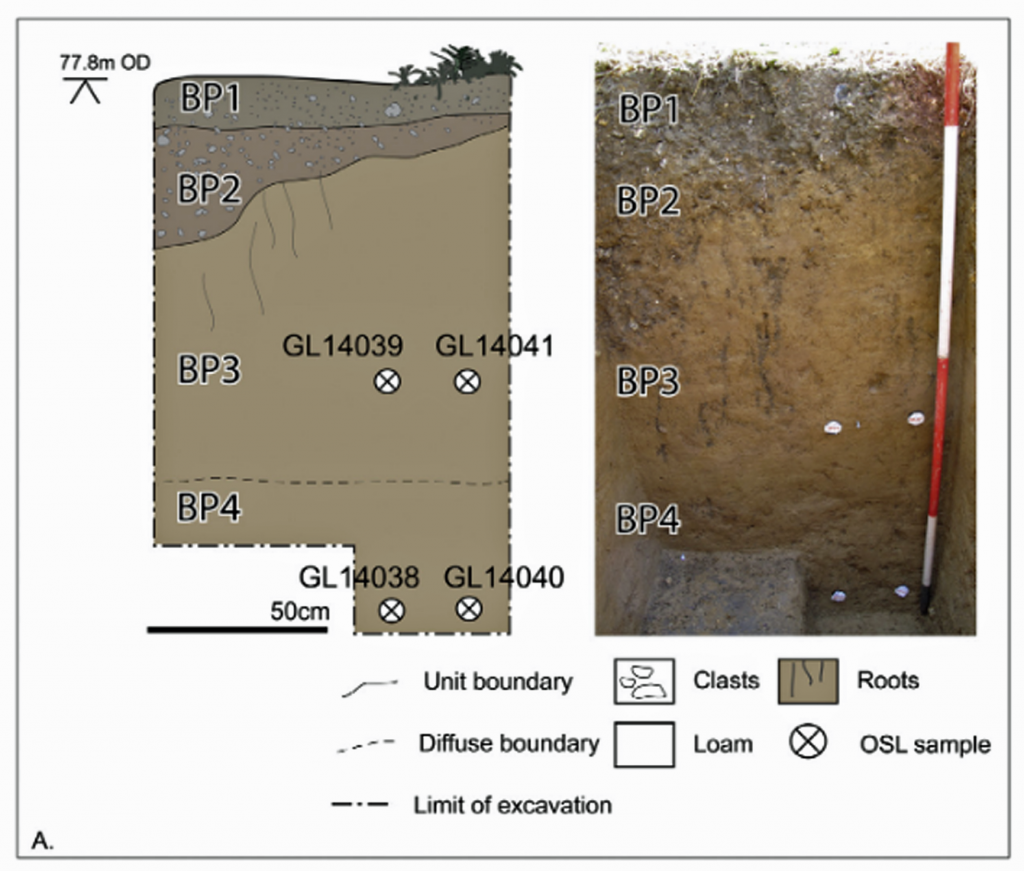

Moreover, when we look at this new method of dating we are not fully assured of its accuracy – as seen by the dating of some sediments at the same soil levels (shown in fig. 62) sample GL 14039 was dated as 70ka +/- 8, and sample GL14041 at the same level was dated 58ka +/- 4, and GL14038 86ka +/- 6 and GL14040 70ka +/- 4.

Not only indicating questionable dates at the same level (almost within the error limits) but moreover, the amount of sediment laid down over from topsoil to first two samples 62ka for the 83cm depth (1.33 cm per 1000 years) and then just 16ka for another 70cm (0.23 cm per 1000 years). This would naturally question the accuracy of optical dating. We believe that history maybe repeating itself as with radiocarbon dating which took over 50 years to obtain accurate results – as it is a new science.

This is confirmed in a 14C v OSL dating paper (Gaigalas, 2000) when they concluded on their results “The observation of an anomaly high OSL age (from 39+/- 4 to 40 +/- 2 ka) for sands which covered the peat layer with 14C dates 24,430 +/- 210 of organic detritus, 27,800 +/- 340 of carbonate tuff…. Strongly suggests that these sands were exposed only for a short time.”

This paper showed that the OSL dates are as much as 30% to 40% older than comparative radiocarbon dating. This is confirmed in the dating range in Fig.60 and illustrates that the ‘Undif.’ Terrace should have been dated to the end of the LGM, as it is clear evidence of recent higher river levels from the meltwater of the last ice age.

What also was missed by the report, was the evidence (as previously shown in our case studies) that the number of river flooding’s (reported by Macklin et al.) that occurred in the Holocene and consequently must have flooded some of the older Avon river terraces. We suspect that is why the terraces between T7 and T10 are of river silt and OSL dates that are out of sequence to the above and below terraces.

“There are obvious problems with uplift modelling based on relative altitudes of terrace deposits and the use of the Palaeolithic record as a chronological marker, and indeed the age proposed by Maddy et al. (2000) and Westawayet al. (2006) for T7 (Woodgreen Palaeolithic site) is not in agreement with our chronometric date of 389-243 ka”. (Egberts et al.,2020)

And this apparent problem is compounded by the fact (which we have also shown) that during the period 389 – 243ka the sea level analysis shows that the ice caps during this period was of a LESSER extent that the last LGM and therefore would affect and flood the river terraces less rather than more!

Moreover, what we agree is the sentiment of Egbert et al. (2019) “The reinvestigation of archaeological sites in the Avon valley shows that terrace deposits offer an opportunity to provide a valuable relative chronological framework but that in conjunction with chronometric age control and accurate height and deposit thickness modelling, a far better appreciation of the complexities of the system and diachronic evolution can be achieved. The more detailed understandings of landscape evolution which can be realised have direct implications for our interpretations of hominin landscape use, behaviour and predictive modelling of Palaeolithic sites”.

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.